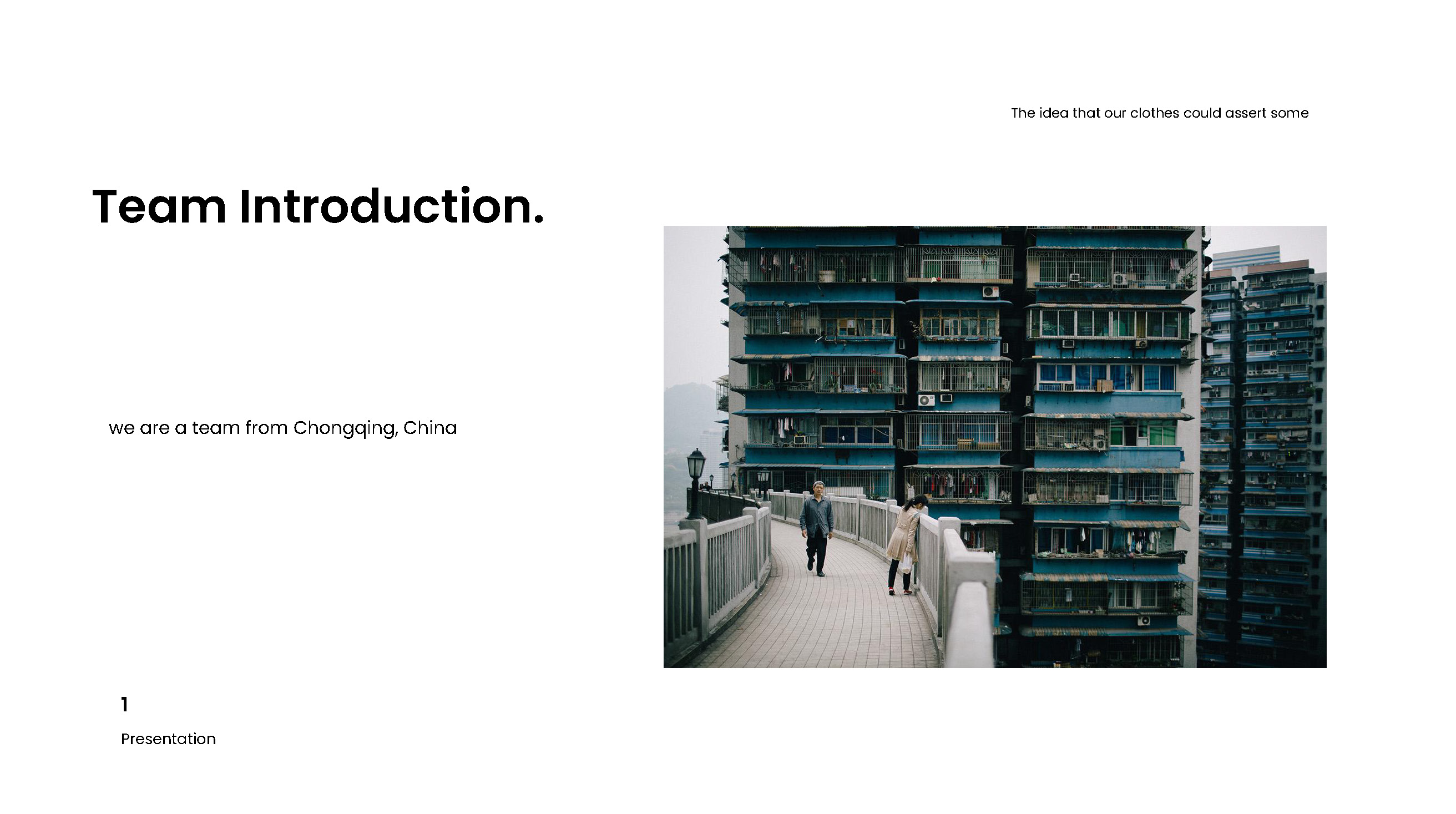

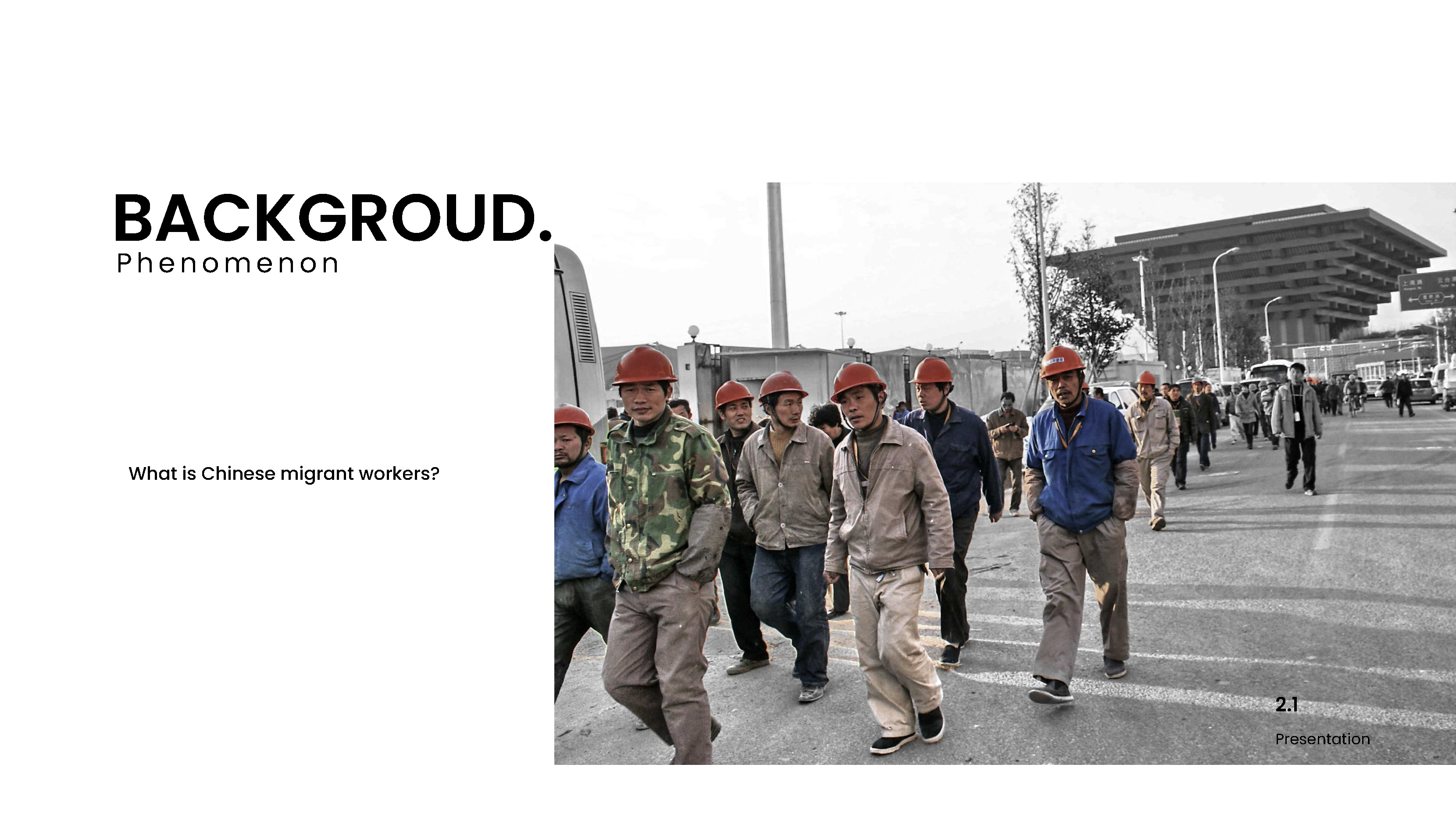

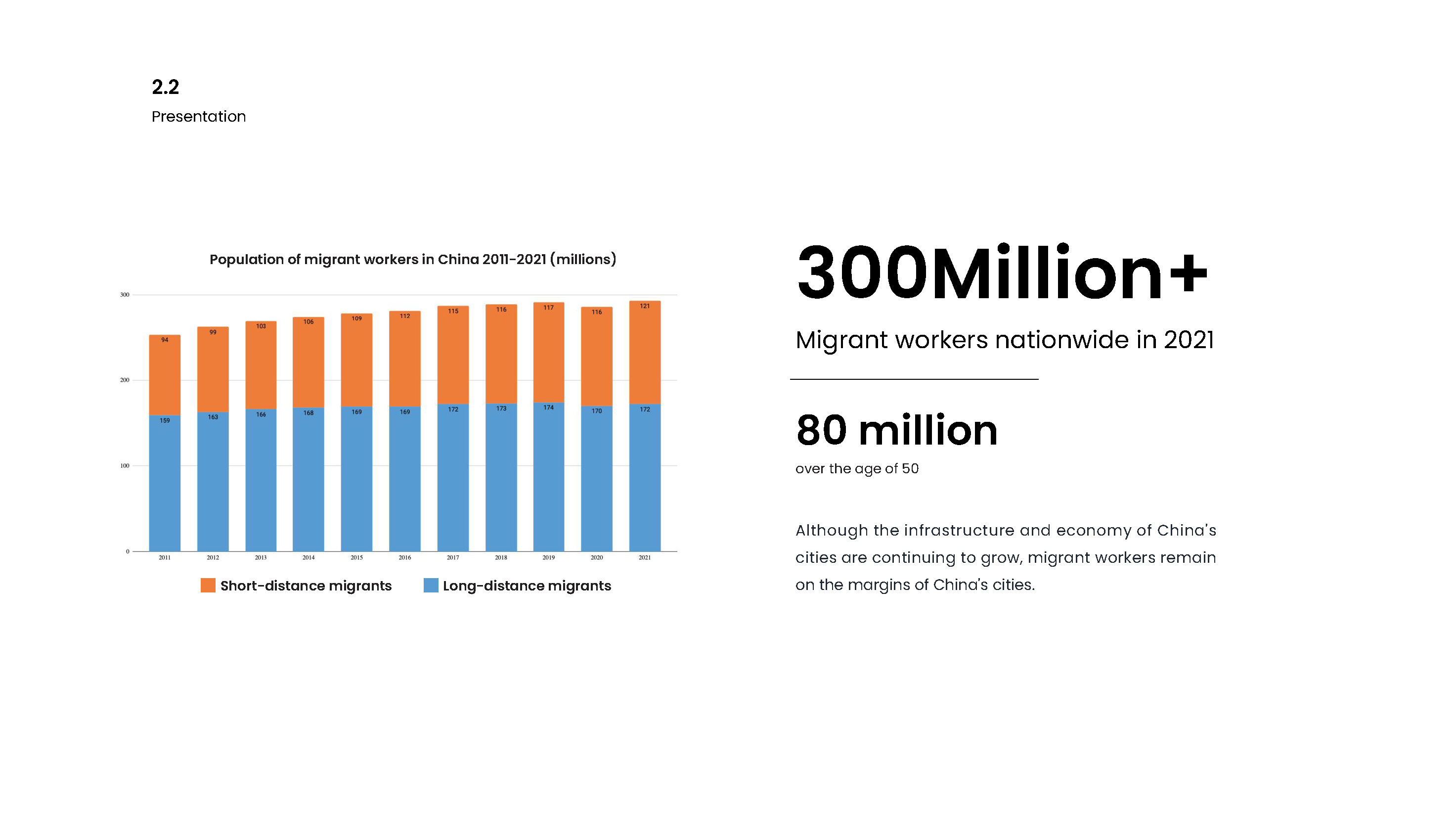

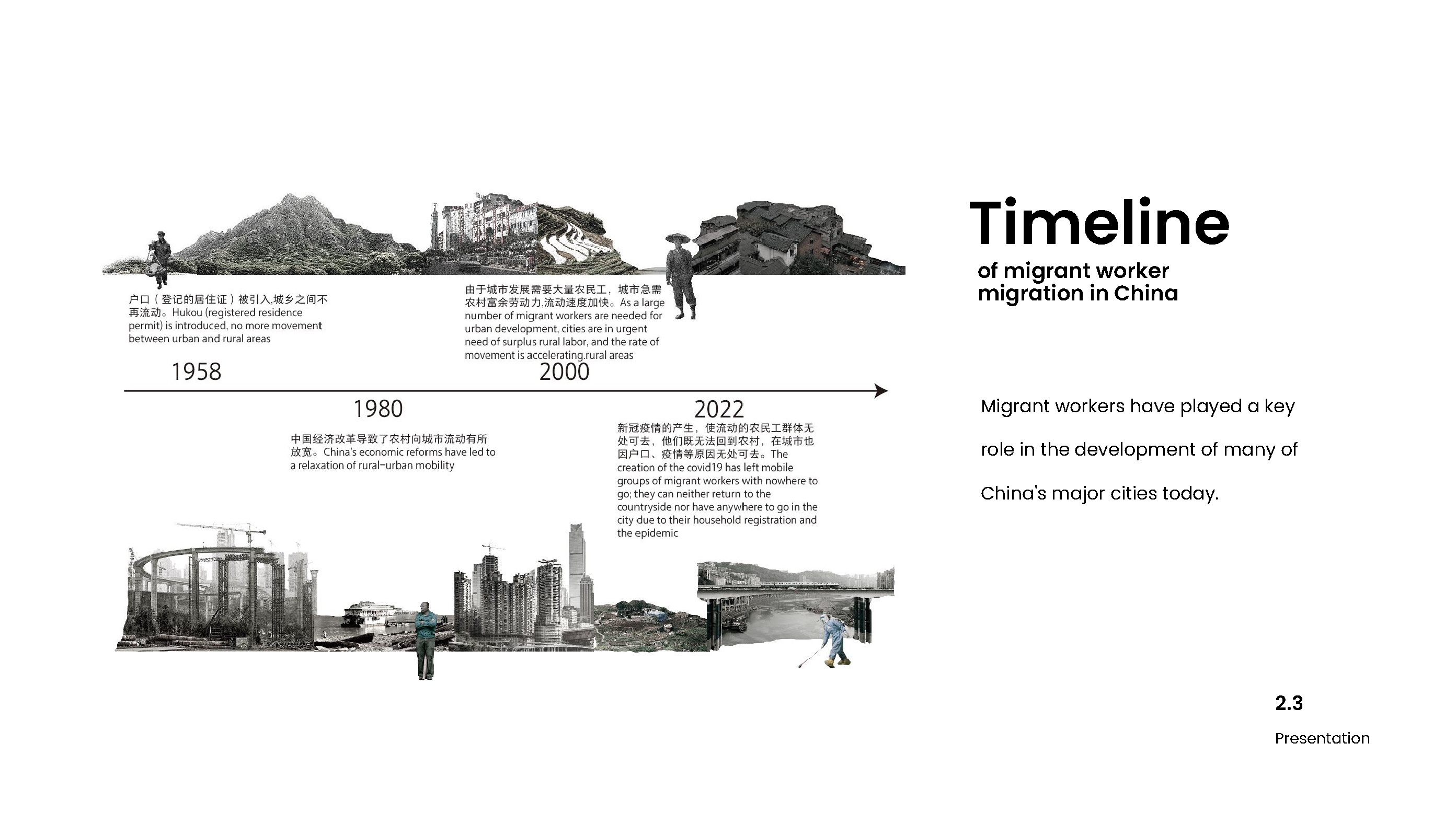

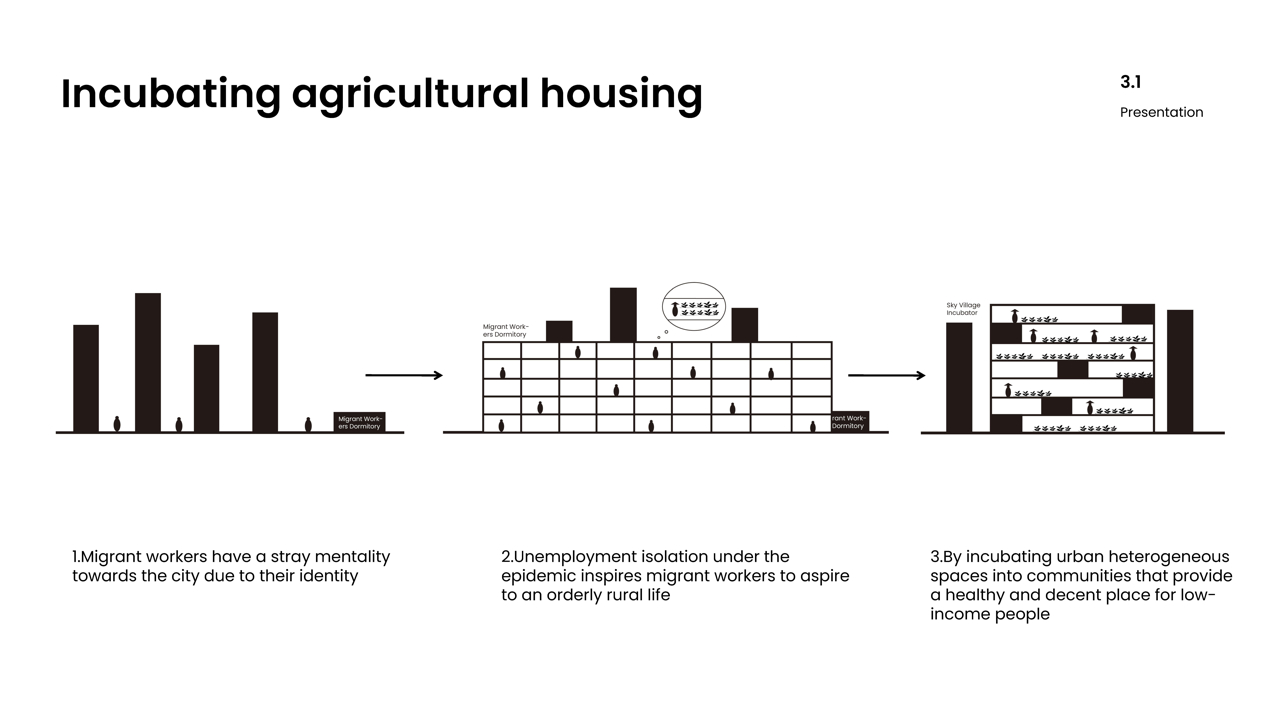

As China's urbanization accelerates, millions of peasants leave the land to work in cities every year. 300 million peasant workers nationwide in 2021, and 27.3% of peasant workers over 50 years old, or about 80 million people, are still on the margins of China's cities, although the infrastructure and economy of China's cities are continuing to grow. As the largest megacity in southwest China, Chongqing has a resident population of over 30 million, nearly half of whom have rural hukou. Due to Chongqing's rapid urbanization, the majority of this rural population has chosen to move to the city in search of a better life and more job opportunities. The urban hukou (China's household registration system), which is the foundation for living in the city and provides access to public services, health care, and education, is highly stratified and segregated, with eligibility based on education level, skills, and status. The hukou creates a divide between urban residents who enjoy privileges and rights and migrant workers. Although migrant workers are indispensable, in practice they have nowhere to go and cannot claim the same "city rights".

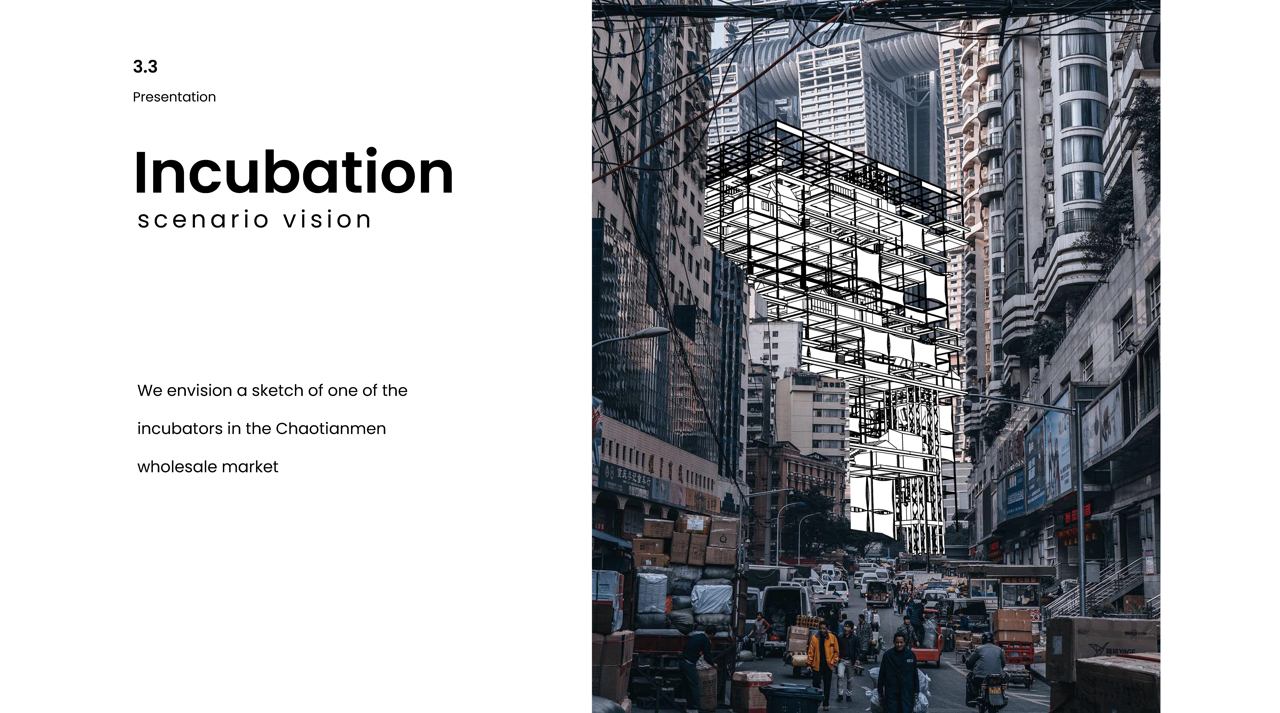

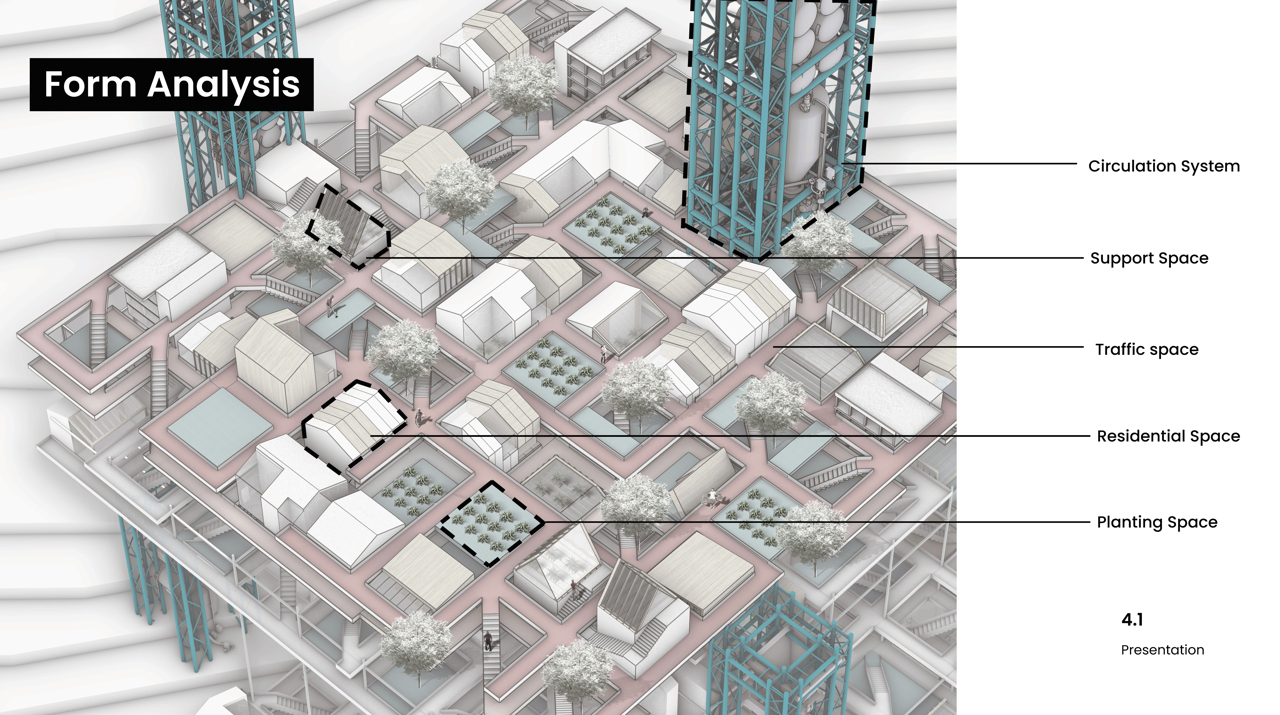

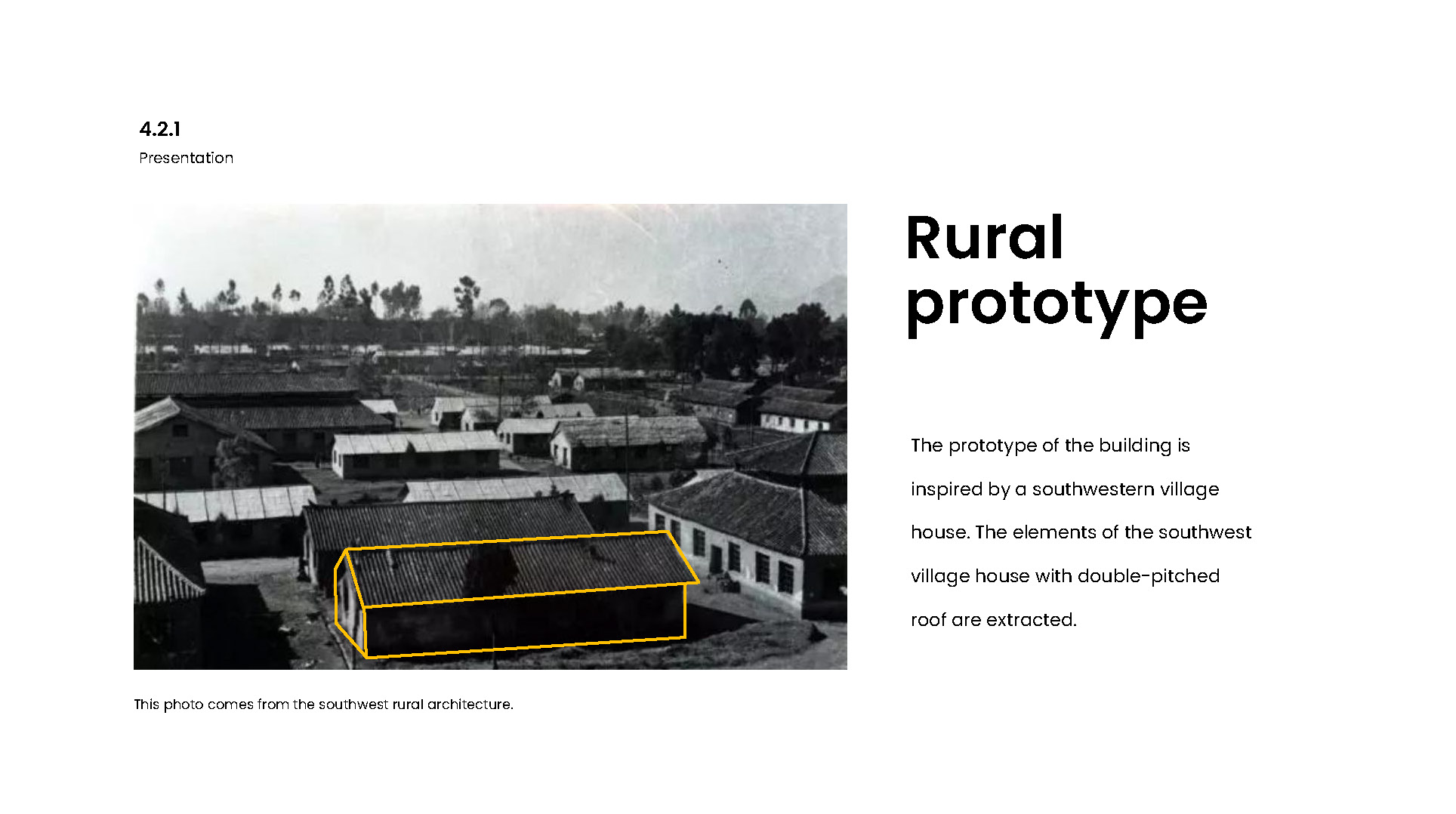

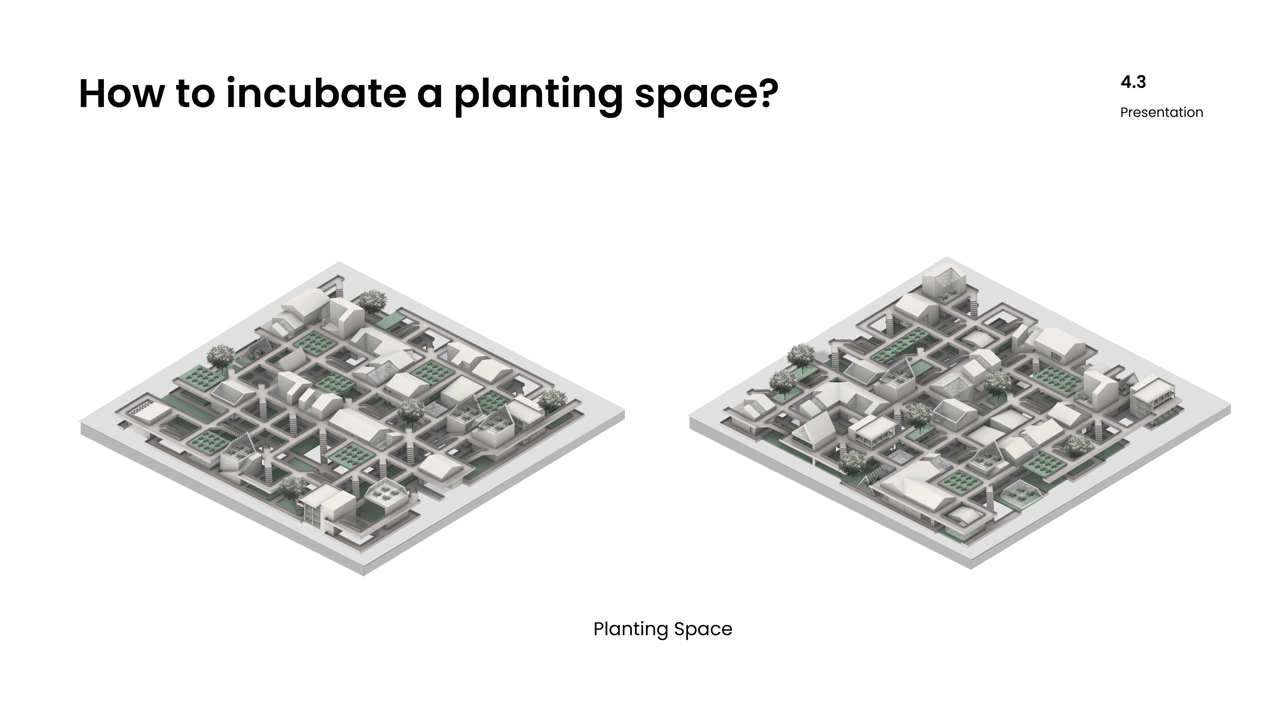

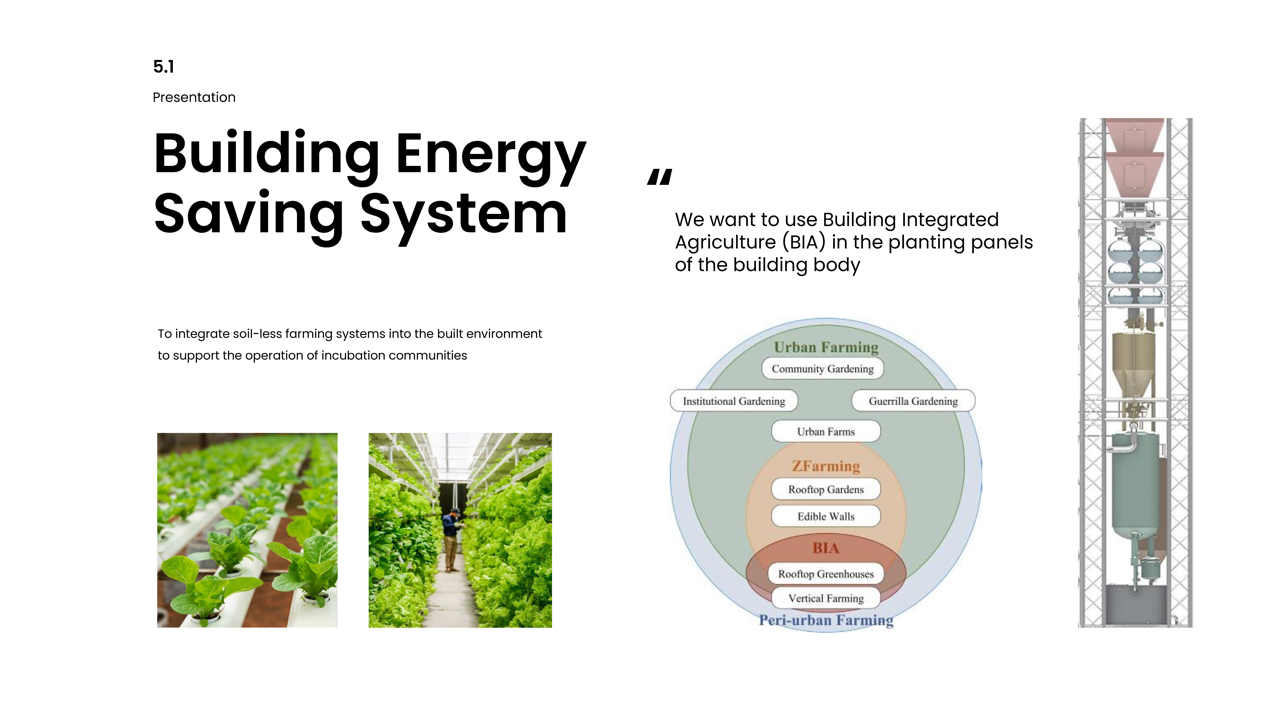

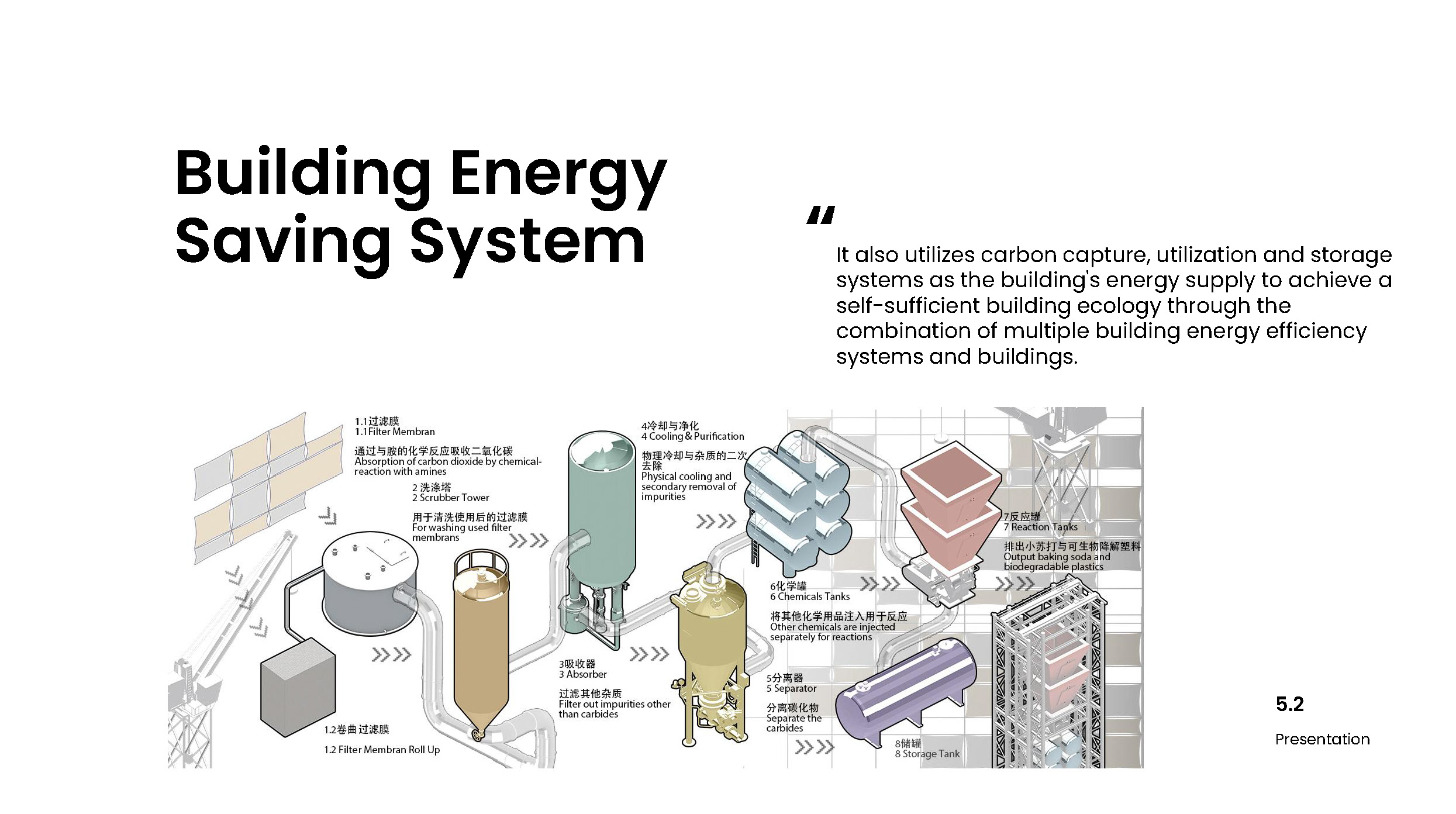

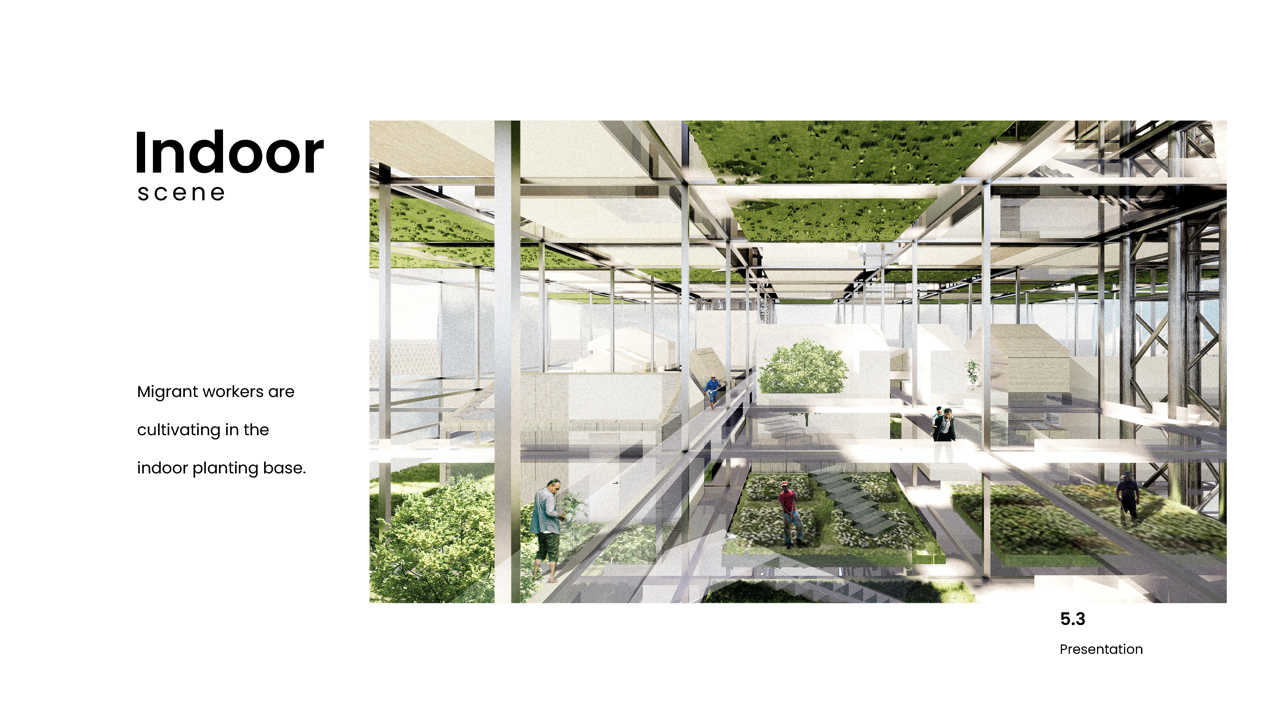

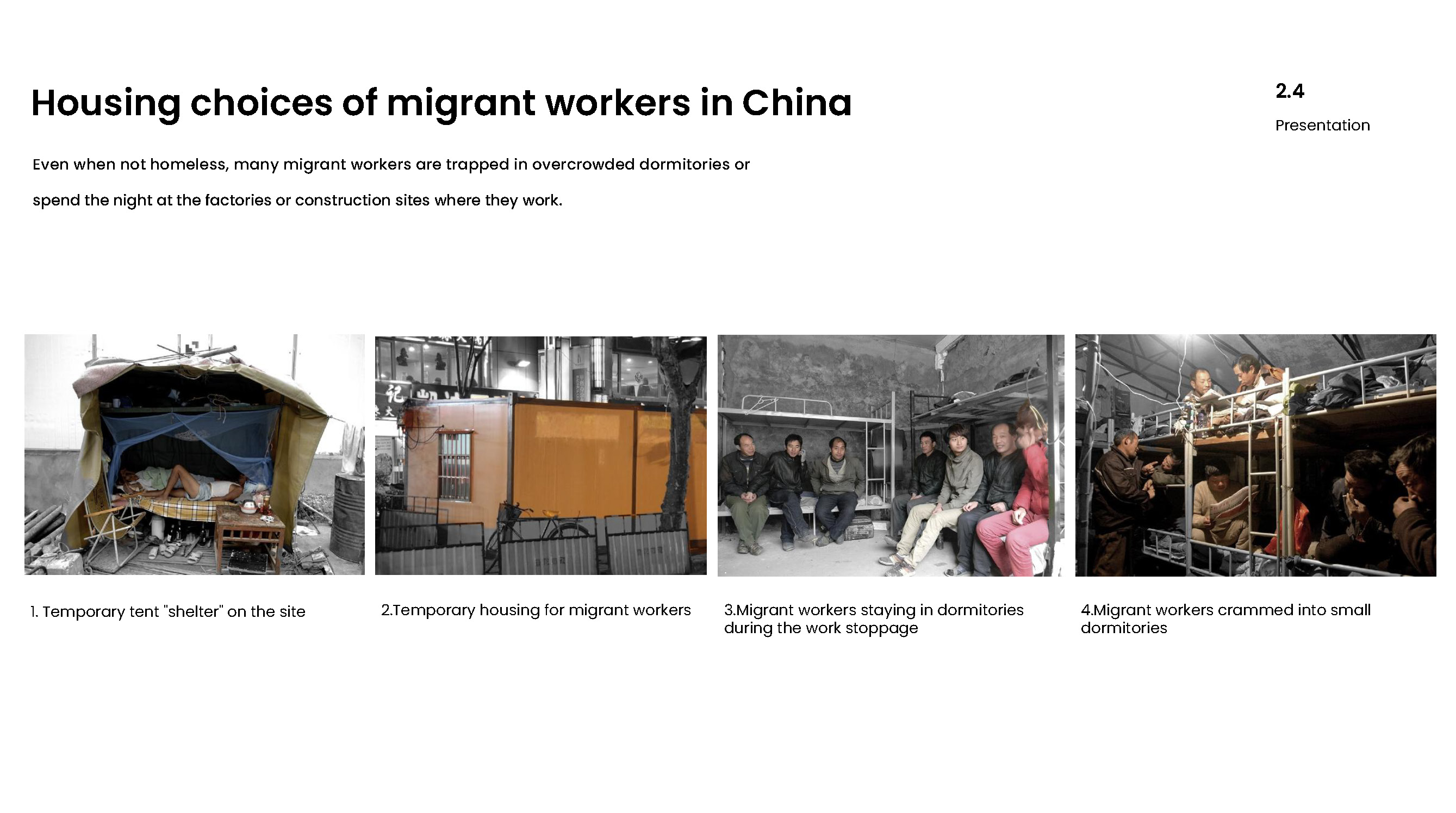

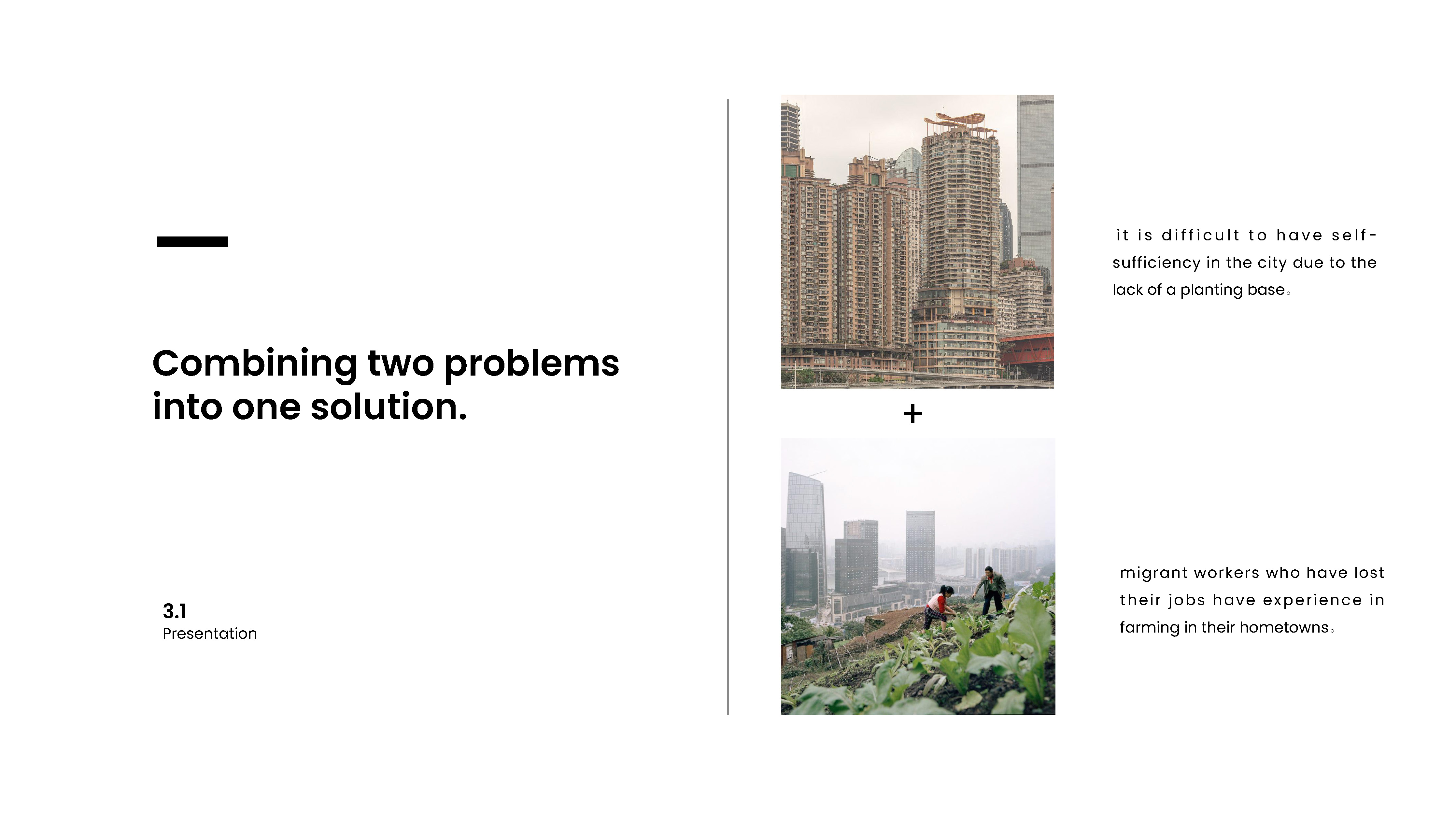

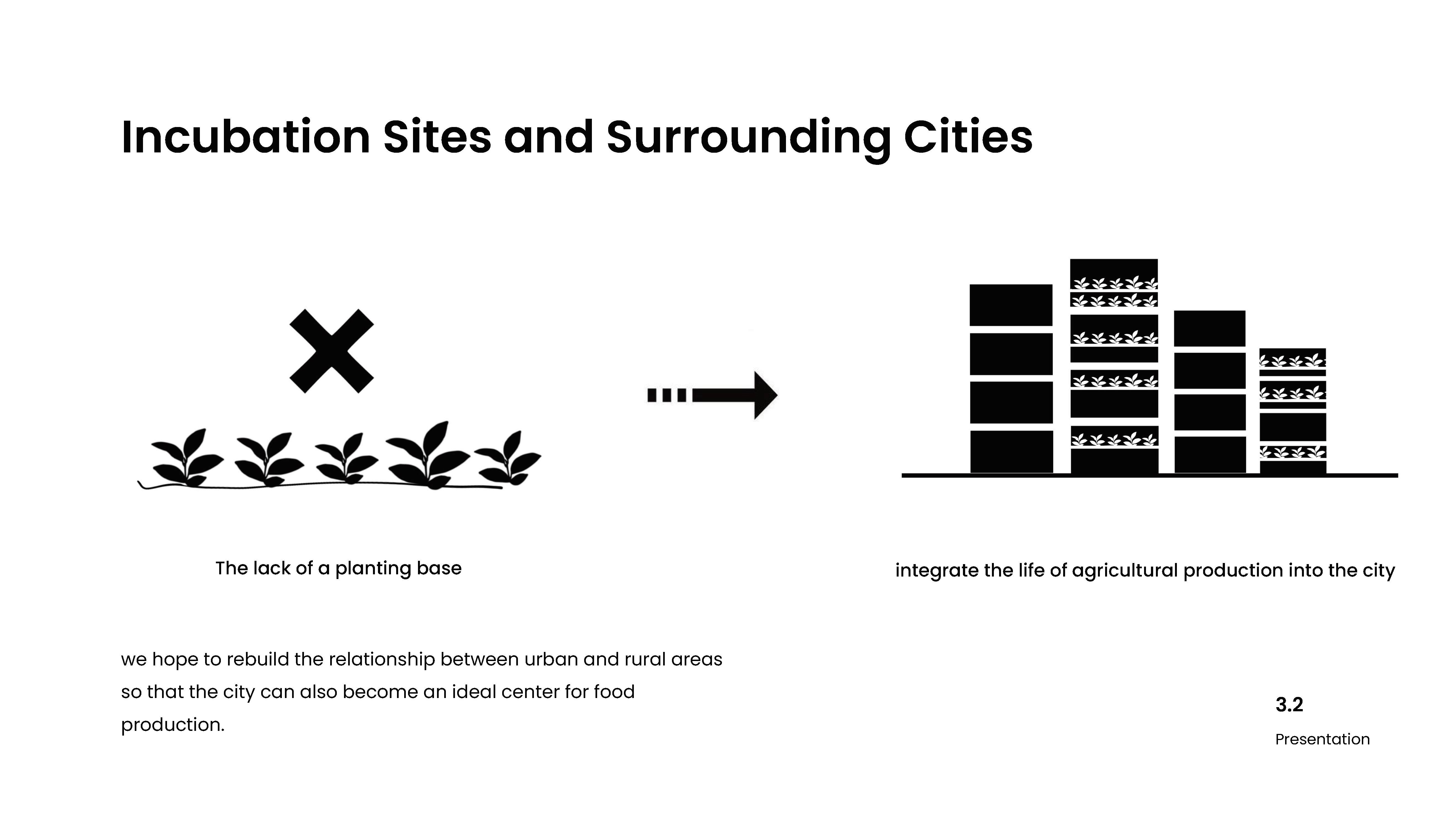

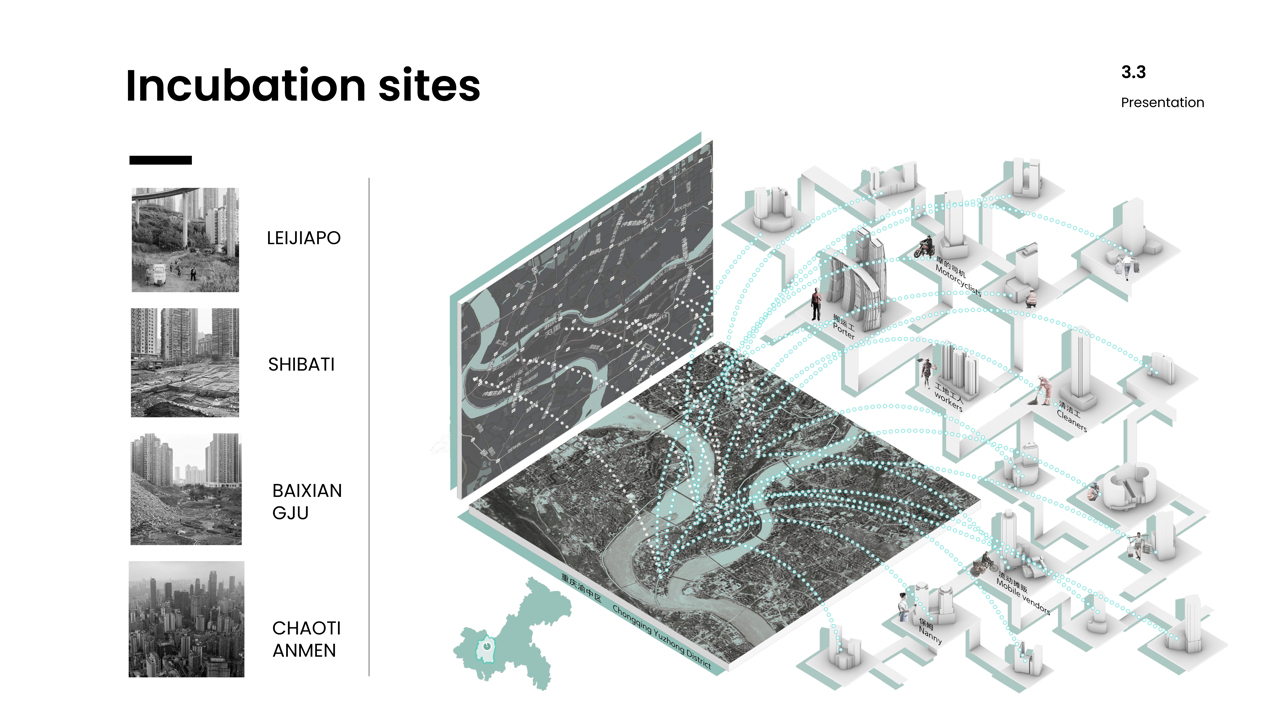

Because migrant workers' job opportunities and apartments are mobile and temporary, the emergence of the new coronavirus has created uncertainty in their lives, and blockade policies leave migrant workers often without other options for employment and accommodation. Even when they are not homeless, many migrant workers are stuck in overcrowded dormitories or spend the night in the factories or construction sites where they work. We took note of this phenomenon and tried to establish a temporary shelter that could be set up quickly to take in these people. In our research, we found that in the event of a major accident, it is difficult to have self-sufficiency in the city due to the lack of a planting base, and that migrant workers who have lost their jobs have experience in farming in their hometowns, so we combined the two problems into a single solution, hoping to insert a planting base into temporary housing that would both house idle migrant workers and provide food for the surrounding community. We first identified incubation sites by looking at the gathering points of farmers in Chongqing's Yuzhong District: Chongqing Eighteen Steps, Chaotianmen, Baixiangju, Leijiapo, etc. These sites typically have large-scale plots allocated for public use by development authorities, underutilized space on streets and edges, and dead space in and around public infrastructure. The largest percentage of these vacant areas are untouched and reserved as green fields and brown fields, suitable for planting.

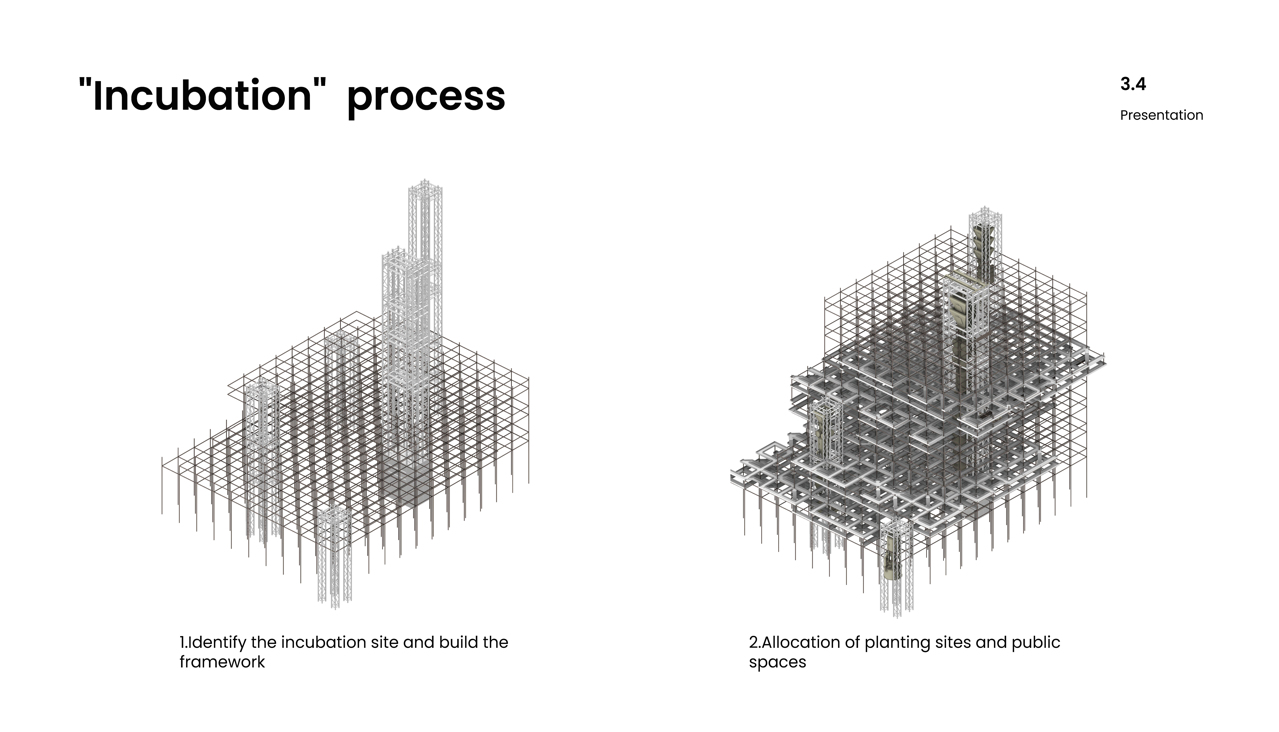

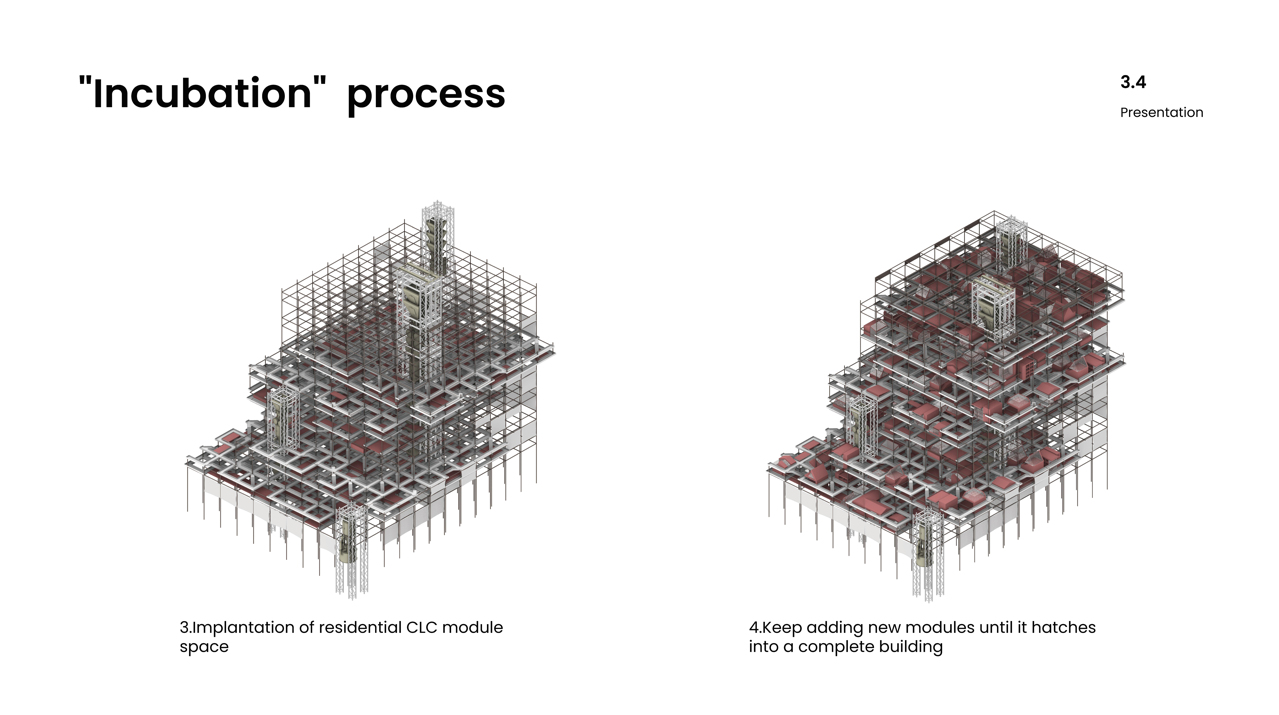

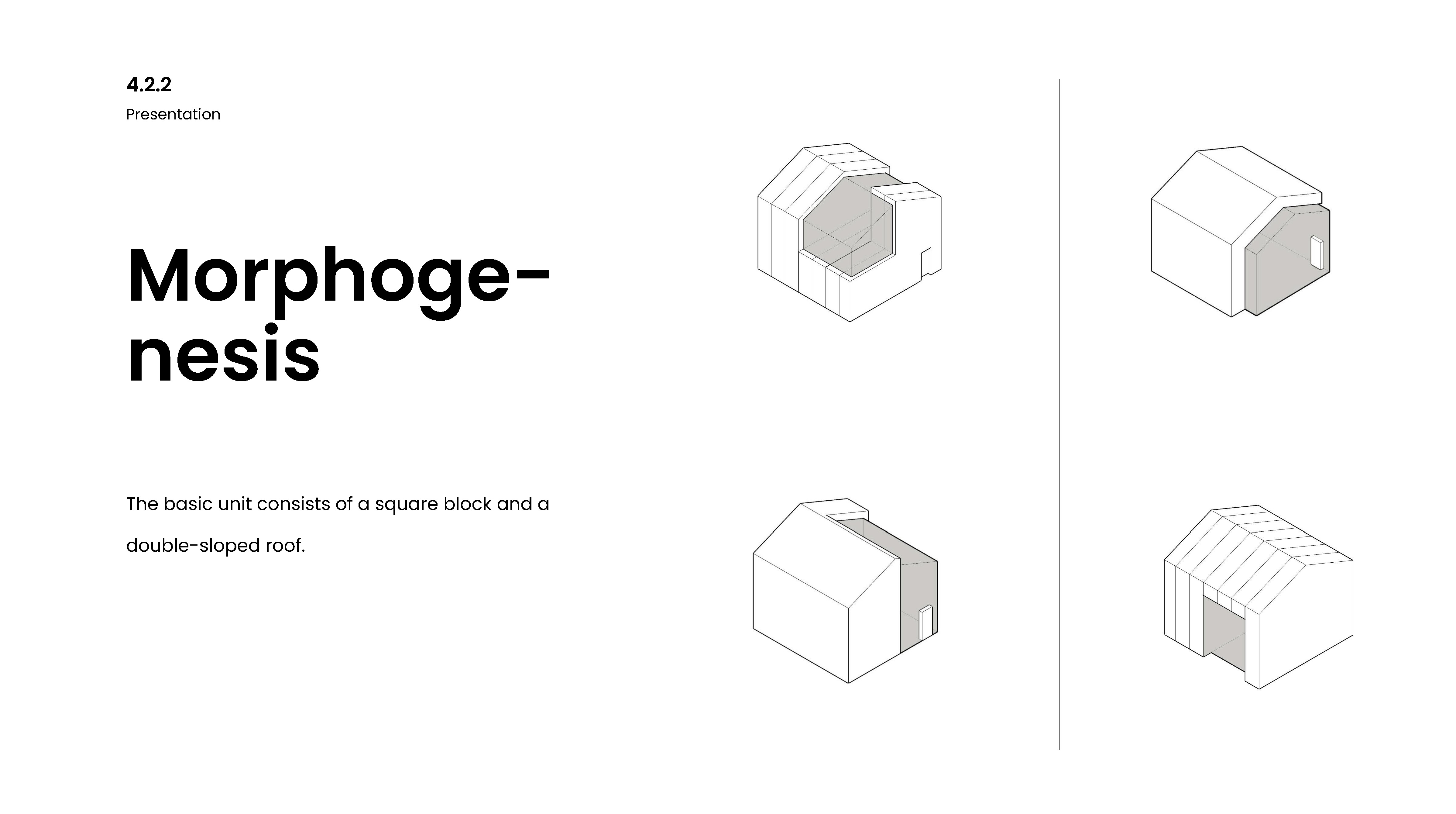

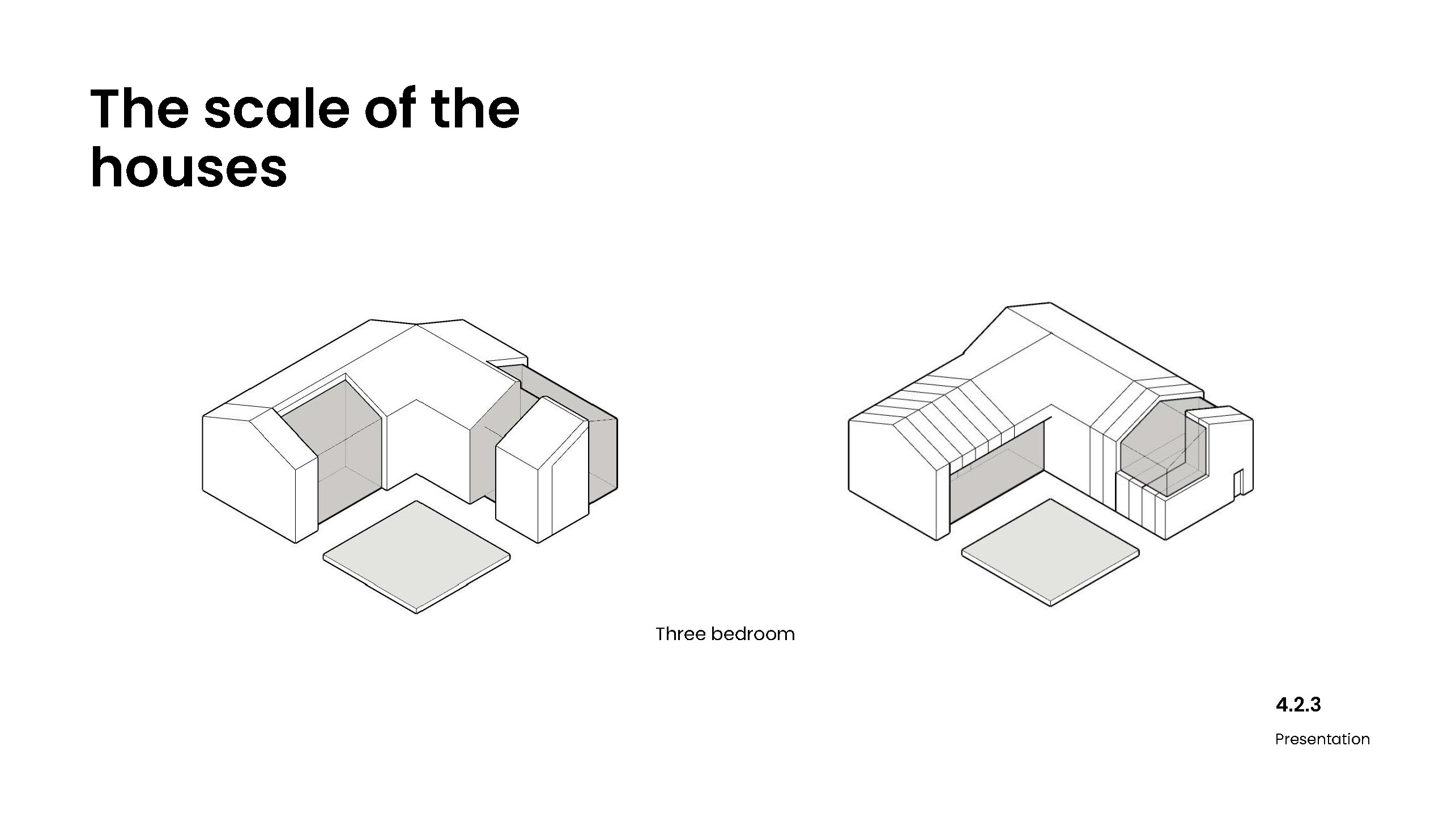

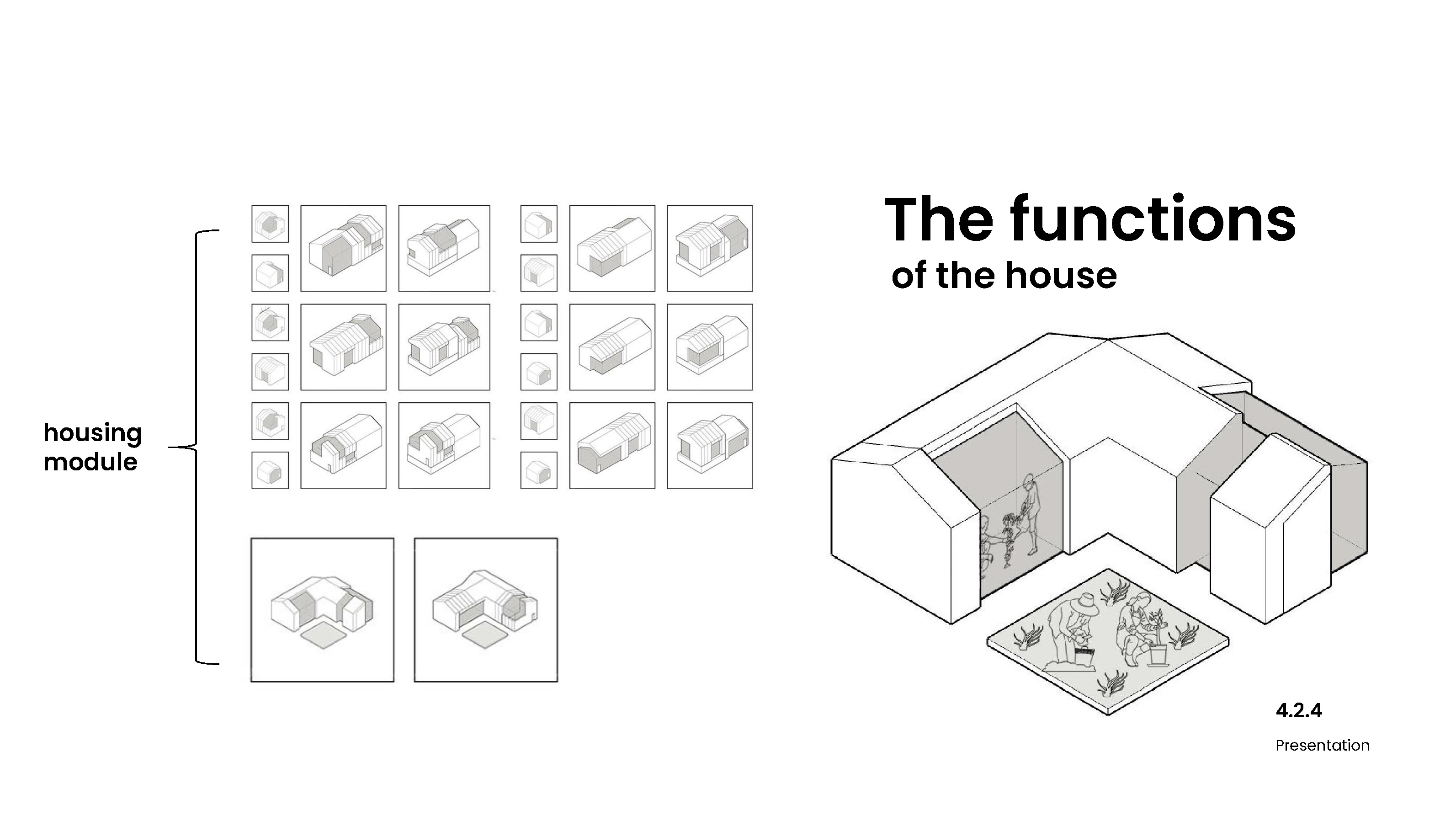

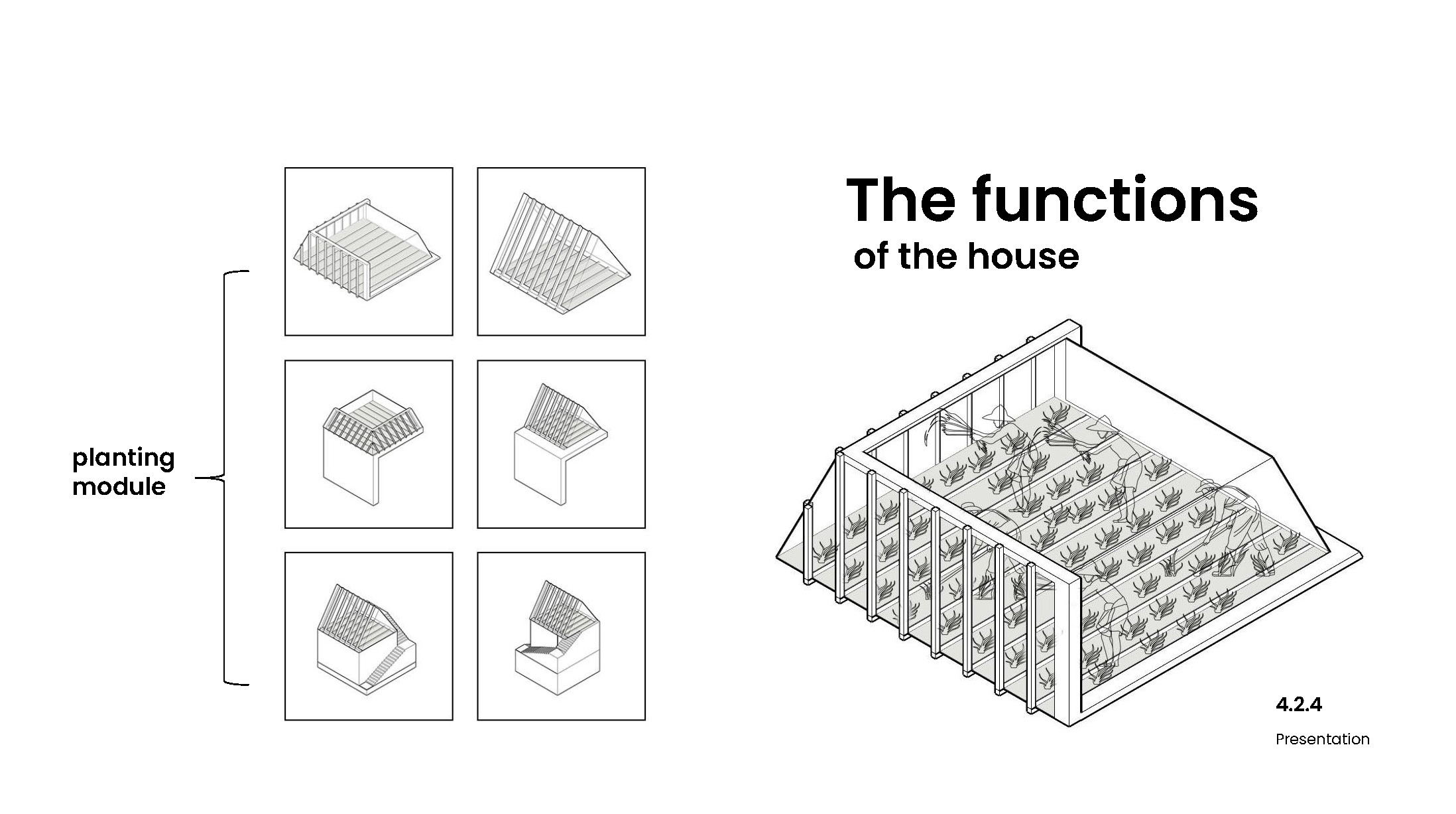

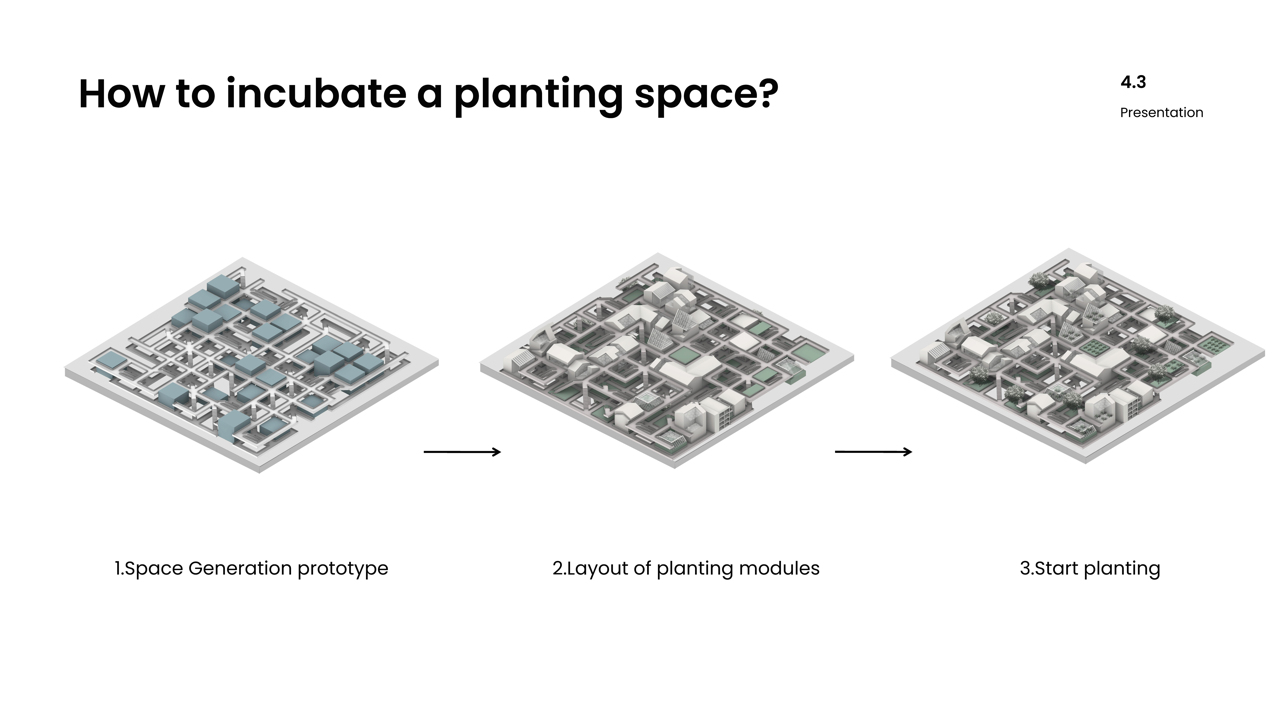

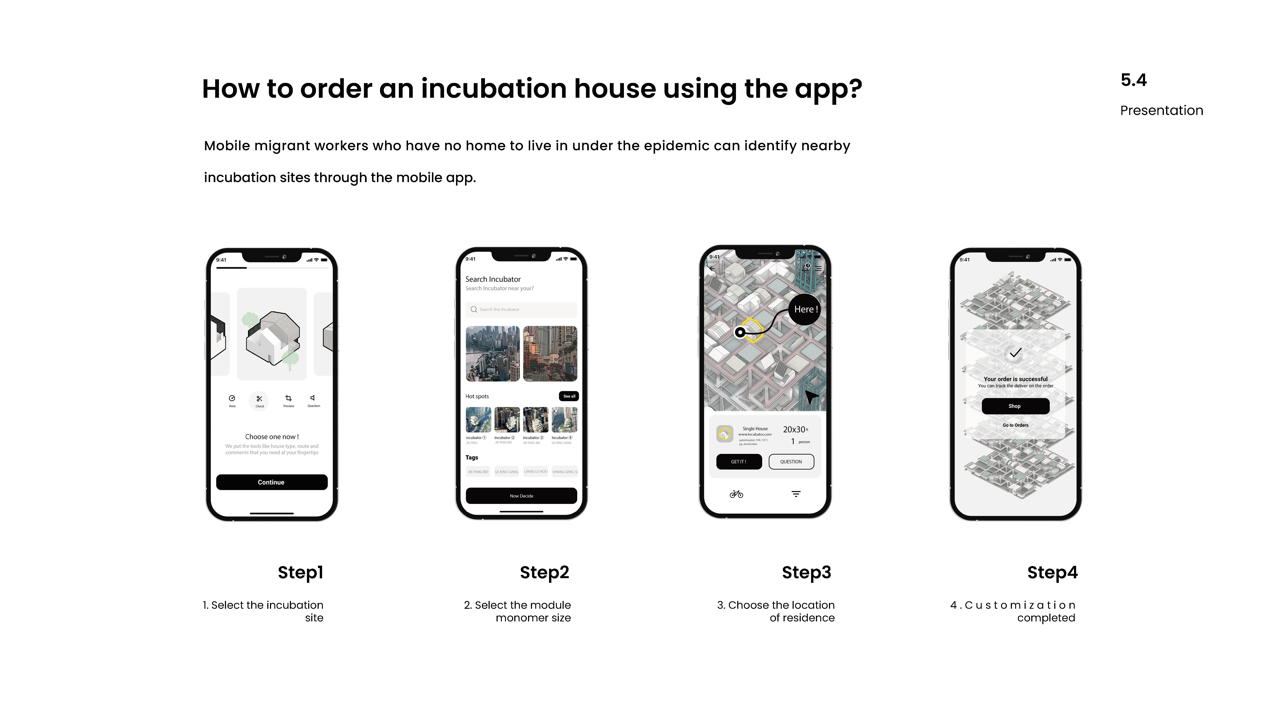

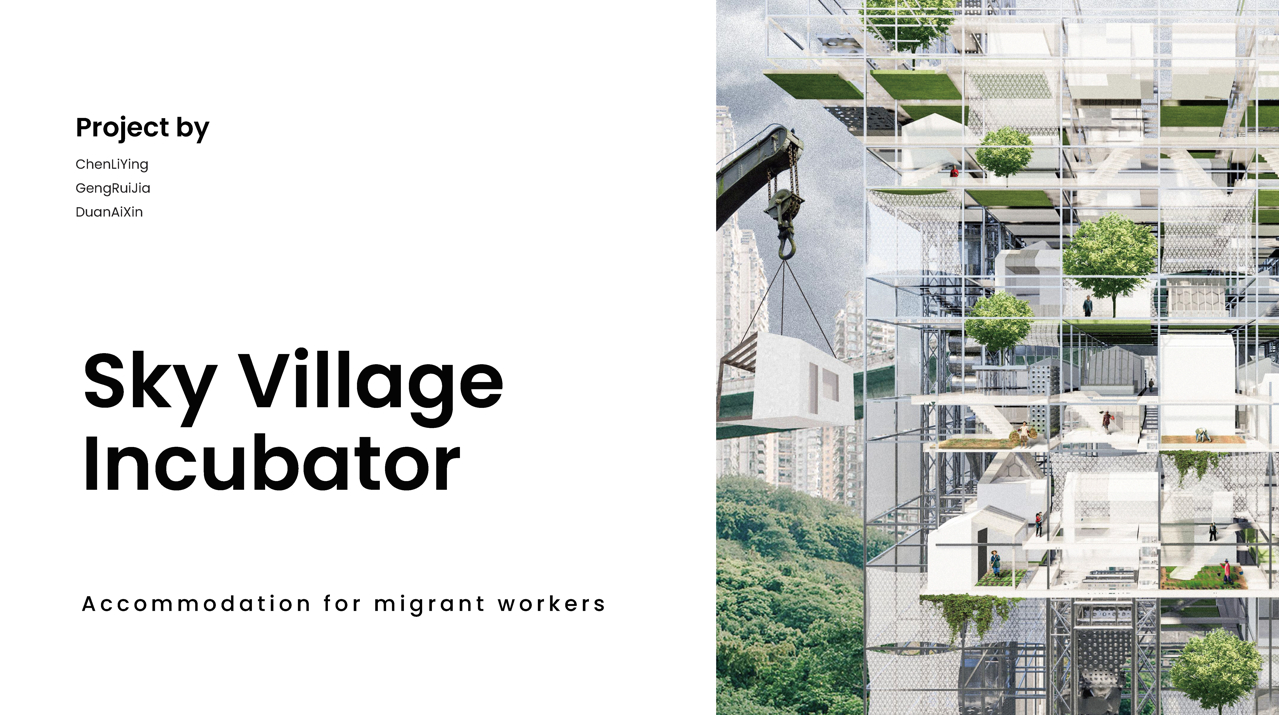

The building started with just the frame, and then the modular building system kept building, and we likened this process of building a home to incubation, as if it were growing and incubating from the bottom up. In this process mobile migrant workers who have no home to live in under the epidemic can identify nearby incubation sites through cell phone apps, and determine the module single house type according to the number of residents, and then choose the location of living inside the incubation village and assign the planting base near the living site. As the number of people in the incubation village increases, its scale becomes larger and larger until it is incubated into a complete building - an integrated urban agricultural settlement.